When Erika Andreeva secured a comfortable 6-3 6-1 win over her younger sister Mirra in Wuhan earlier this week, there was understandably no hint of celebration.

It was the first time the Russian siblings had faced off in a professional match. It was also the first WTA match contested between two sisters since Serena and Venus Williams’s final encounter in 2020. Ahead of the match, Mirra confirmed that they had agreed to split the prize money from the match, whoever won.

Though Mirra, 17, is the precocious top teenager and the higher ranked (making her top 20 debut this week) sister, her elder sister won out this time. At the net, a wordless hug was exchanged, before they moved off the court with haste.

Though they will have practiced together countless times over the years, it must feel very strange to look across the net and see your sibling during a professional match.

Even suppressing a celebration must feel bizarre when you consider how competitive top athletes are. No doubt, the pair have spent their entire childhood taking wicked enjoyment out of beating each other. You don’t have to be an elite athlete to understand the very unique feeling of getting the better of your sister or brother in any competitive endeavour. Whether on the tennis court in a low-quality doubles match on a family holiday, a Christmas Day marathon game of Monopoly or simply completing the daily New York Times mini-crossword in a quicker time (or is that just my family?), that smug winning feeling cannot be replicated.

But as Erika won 11 of the last 12 games of her match against Mirra, there were mixed emotions. "It was tough for both of us," Erika, 20, said afterward. "First experience, and both of us were happy it happened at a big tournament. But I'm not sure we enjoyed it."

Even the Williams sisters, two of the greatest players in tennis history, have admitted to losing some of their ruthlessness when up against their closest confidante. The Andreeva meeting actually came in the same week I’ve been bingeing Serena’s newly released ESPN documentary series, In The Arena: Serena Williams. While the series is not perfect, and Serena (who executive produced the programme) was clearly selective about what went omitted, some of the most insightful moments came when the Williams sisters reflected on how it felt to play against one another.

Serena admitted that, when they were children, she would “cheat” by calling Venus’s shots out in the practice matches they would play. But once they went pro, there was an uneasiness when they stepped onto the court on opposite sides of the net.

Serena defied the natural order by winning a Grand Slam title before her older sister did, when she clinched the 1999 US Open aged just 17. There was a twinge of guilt amid the joy. “I think I was probably happier than Venus when she won Wimbledon [in 2000],” Serena said in the documentary. “Because it felt like ok, I’m not stealing anything [from her].”

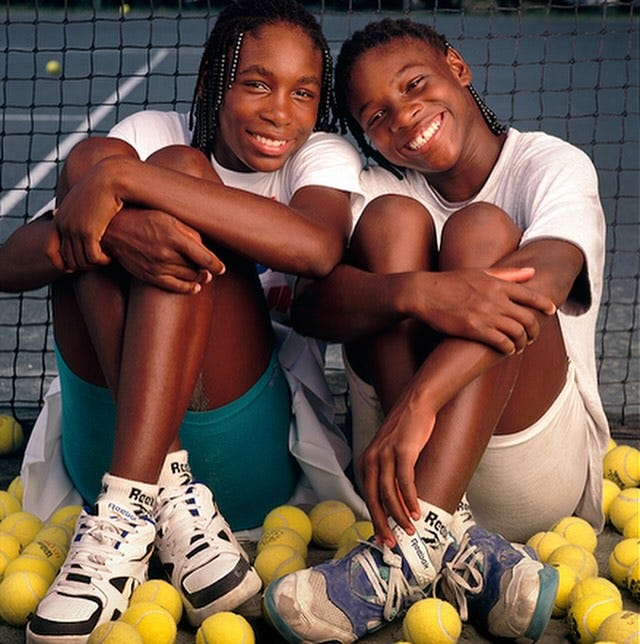

These two players shared a hotel room at most tournaments in their early years, practiced together, ate together in the player restaurant and shared the same coach, their father Richard. They also felt a certain frostiness directed towards them by some of their rivals, and that only cemented their family unit further. Trying to beat each other on court went against their instincts. But being the two best players in the world meant they had to do it many times, on some of the biggest stages in world sport.

Between the 2001 US Open and 2003 Wimbledon, six out of eight major women’s finals were Venus vs Serena. The matches were always hyped up, but they often fell slightly flat. The crowds felt conflicted about who to support, their applause more muted than you’d expect, and neither sister could behave with the same passion they usually brought to the court. It verged on awkward at times.

Serena could not even look at Venus on the other side of the net during those matches. It was the complete opposite tactic to her usual trademark, where she imposed herself on her opponent with long glares and targeted point celebrations. But it worked and, unfortunately for Venus, Serena won five of those six initial Grand Slam finals.

Over their entire careers, they played 31 professional matches against each other (12 coming in finals), with Serena holding a 19-12 winning record. They also won 23 doubles titles together.

No sibling rivalry even comes close to the Williams sisters, but there have been many other famous siblings in tennis. Andy and Jamie Murray both reached world No 1 in their chosen disciplines (singles and doubles respectively) at the same time. Bob and Mike Bryan won 119 doubles titles together. Dinara Safina and Marat Safin both reached world No 1 in singles on the WTA and ATP rankings respectively. Manuela, Katerina and Magdalena Maleeva of Bulgaria all were ranked in the top 10 - the only trio of sisters to ever achieve that. The Andreeva sisters have tons of inspiration to draw upon.

It is a sport where family projects reign and today, as 38-year-old Rafa Nadal announced his retirement while I wrote this Substack, my thoughts turned to his own family story.

Much will be said about him over the next few days: how he was ferocious on the court, a physical specimen unlike any tennis had ever produced, and that — even after winning 22 major titles — he remains humble to a fault. The other part of his story is how it is another example of tennis staying in the family.

As a child, Nadal had his pick of world-class tennis academies, but he chose to develop his talent at home, in Mallorca, under the tutelage of his uncle Toni, a relatively inexperienced coach. Uncle Toni would help guide him to 16 major titles, in a partnership few — except the Williams sisters and their father Richard — can come close to. Nadal may have gone on to win just as many without Toni, we will never know, but he definitely served as a grounding force unlike anything his immediate rivals had.

Upon the evidence, no one can push you to be great quite like a family member can. There are plenty of horror stories you can find within that rule (especially in tennis), but it can also provide some of the most wholesome narratives in sport.

Last week, I published the latest episode of my Off The Bench podcast, where I spoke with Becky Downie, one half of gymnastics’ favourite sibling story. She and her sister Ellie won World Championship medals on the very same day in 2019, reaching their sport’s pinnacle at the same time, even though they have a seven-year age gap. During the episode (which you can listen to here), we discussed how she and her sister found strength in each other’s experiences when they became whistleblowers for abuse in their sport. Becky also said that in passing her love for gymnastics down to her younger sibling, they discovered a raw talent in Ellie that far surpassed her own.

It’s a sentiment often backed up by research, which has found elite athletes are more likely to be younger siblings and, even when both siblings reach elite sporting levels, the younger one often has better results over their career. This piece by Tim Wigmore for FiveThirtyEight is a great read on the subject.

Meanwhile, a new branch of sporting family history was made this week in the NBA pre-season: LeBron James, 39, and his son, Bronny, 20, became the first father-son duo to play on court together for the same NBA team, the Los Angeles Lakers. “Wow, that was surreal,” LeBron said afterwards.

Multi-generational success is not uncommon across sport, but achieving it at the same time is quite the feat. As top athletes are pushing their bodies into new realms, continuing to play late into their 30s and even early 40s, this is the newest measure of greatness: can you compete with your offspring? Nadal never got the chance (his son just turned two), but forever-young Novak Djokovic hasn’t yet ruled out the possibility.

The pressure experienced by the less talented sibling must be hard to take, but being the less talented son or daughter must be even harder (just ask Romeo Beckham, currently a member of Brentford’s B Team).

In Bronny’s case, let’s be real, he will never eclipse his father’s greatness as the all-time record point-scorer and a four-time NBA winner. That alone would be enough for most people to avoid the sport and maybe aim for greatness in another field. So you have to at least respect him for putting himself out there at all, especially after experiencing a cardiac arrest during a practice session only a year ago. There will undoubtedly be more eyes than usual on the G League this season, where Bronny is mostly expected to play his rookie year.

Some have understandably cried nepotism, saying it’s just a vanity project for LeBron, while others are already lapping up this new career arc for him as diehard fans. Regardless, the James story will be one that captivates this season — family dynasties always do.

Recommendations

I expect many of you will join me in mourning the end of Nadal’s career, so here are a couple of watches/reads on the man himself that I’ve spotted in the hours since his retirement announcement broke.

This tribute by Jon Wertheim for Sports Illustrated (featuring an unexpected littering anecdote) is great. The documentary Strokes of Genius (inspired by Wertheim’s book of the same title), about Nadal and Roger Federer’s 2008 Wimbledon final, is another gem, which you can watch on Apple TV.

And if you have time to go full-on with the nostalgia, just watch the 2008 Wimbledon final in all its six-hour glory on YouTube here (there’s no shame in it, I’ve done it before and so have four million other people according to the views).

Thanks for reading!

Molly x